This is a picture of Benjamin, his wife Mary and their 10 children. Names are listed in the history of Mary Lewis.

Here is the story of one man and a tenth of his family, and their part in the development of the west. Here, perhaps, is not a typical family, but not a highly unusual one. And here is some of the bone and sinew of America, some of the fiber of the West.

The story does not begin, nor does it end, on the beautiful western Autumn day in 1939 in Brigham City, Utah, when Benjamin Lillywhite hobbled, rather spryly considering his ninety-six years, along the widewalk down East Forest Street between the court house and the library to a bench on the court house lawn, but that date and that place put the story in its natural setting.

On the court house lawn Benjamin joined a few other natives of ancient vintage, perhaps twenty years his junior but less able to navigate than he. He squinted his one good eye, the one that had served him for almost seventy years, at the sleepy life of Brigham City and at second and third generation neighbors who had come to consider him a familiar and permanent landmark on the court house lawn. He talked a little in a thin voice to a friend, who could hear no better than Benjamin could, about the war and the wickedness of the younger generation and the fact that he had not been feeling so well of late.

After an hour or so he hobbled back toward the home of his eldest son, Joseph, with whom he had lived for the past several years, three blocks east on Forest Street. As he passed the city hall Benjamin stopped a young man and gave him a brief but vigorous lecture on the evils of the cigarette that the young man was smoking. Benjamin's Mormon religion had told him that the cigarette is a tool of the devil, and he must try to protect mankind from it. Then muttering to himself he continued on home.

That afternoon he read a bit from the Book of Mormon, scanned the Church section of the Deseret News, and carefully read all the world news on the front page of the local paper, mumbling to himself as he repeated half aloud each word that he read. He listened to all the news broadcasts and worried about the war aloud, to no one in particular. He grumbled whenever there was anyone around to hear him; bewailing the fact that he hadn't enough money to buy a car so that he could get himself a young wife and go on a trip. For twenty years Benjamin had wanted these two things, a car and a young wife. What matter that he had worn out two wives and was almost a century old? But for almost ten years he had had to content himself with some such daily routine as described here.

Next morning Benjamin said he did not feel like getting up. He did not go downtown that day. Two days later he died quietly. He had gone to that reward he had been absolutely

certain that his life of righteousness would earn for him; the reward that his religion had taught him would be his in after-life. His belief in a glorious hereafter had been so firm that his last years were spent in eager anticipation of what was in store for him after he died.

certain that his life of righteousness would earn for him; the reward that his religion had taught him would be his in after-life. His belief in a glorious hereafter had been so firm that his last years were spent in eager anticipation of what was in store for him after he died.

The death of Benjamin ended a life that had spanned ninety-six remarkable years in the making of a state and a nation. It ended a life that had seen the infant settlement of Great Salt Lake City develop into the beautiful state of Utah through the strangest history that any commonwealth has ever experienced. And his death took away the head of a family of ten sons and daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren too numerous to account for, and scattered over almost every part of the world. Benjamin's life was typical of the hardy men that pioneered and developed this nation, especially those who made Utah and the West. It is fascinating to contemplate the events and changes that took place in Utah during his ninety-six years, and the enormous family that spread such hardy stock throughout the country.

Some time in the early 1840's Mormon missionaries in London converted and baptized Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Lillywhite, and so fascinated them with tales of the Mormon center of Zion in Nauvoo, Illinois that the Lillywhites sold all their possessions and, in 1847, bought passage on the chartered Mormon immigrant ship to America for themselves, their four-year-old son Benjamin and daughter Sara, age two.

Early in 1848 the Lillywhites left New York for St. Louis in a wagon train. Mother and daughter could ride the dusty miles in a lumbering covered wagon, but five-year-old Benjamin, with father, walked beside the wagon during most of those weary miles, and thus began for Benjamin, while yet a baby, the life of terrific struggle and almost unbelievable hardship that was to be his for almost a century. During the last days of the journey the elder Benjamin contracted cholera; by the time they reached St. Louis he was so weakened by the disease and the travel that he never recovered. He died in June of the following year. Soon after this the infant Sara also contracted cholera and died. So Benjamin junior became Benjamin senior at the age of six, and never again did life allow him to be a boy.

The Lillywhites had arrived in St. Louis to find it a hot-bed of reaction against the Mormons. There for the first time they learned of the murder of Joseph Smith, leader of the Mormon Church, at Carthage. Mormons in Nauvoo were being driven west like leaves whipped before a raging storm. Certainly there was no refuge there for the destitute Lillywhites. And to add to their difficulties a boy, later named Joseph, was born to Mrs. Lillywhite in November of the same year that her husband and daughter had died.

Benjamin Lillywhite Jr. in 1939 with Janet, Marilyn, Jeanne, David and Dick, his great grandchildren.

It was impossible for the mother to remain in St. Louis with her two sons, so she arranged to take Joseph to Utah with a wagon train, but there was not room for three. Consequently, Benjamin was adopted by a couple named Miller, under whose care he began the trip to Utah in a different wagon train. On the plains of Iowa Mr. Miller died, and Benjamin, now nine, drove the ox team the remainder of the trip to Salt Lake Valley, arriving there in September 1852.

Mrs. Miller accepted the practical suggestion of her church leaders to waste no time in grieving or in finding another husband, so she married Mathew Mansfield late that same year. Benjamin remained with the Mansfields until after he was seventeen.

When the Mormons were driven out of Nauvoo, Brigham Young had turned his face to the west with the statement, "If there is a place no one else will have, that is the place I am looking for." In 1852 "Zion" must have appeared, to the new arrivals, like the place no one would have. In the first year of its settlement, 1847, nearly all the work of the settlers had been destroyed overnight by a heavy frost, and later what was left was eaten by crickets. Hunger had stalked every door during that long winter.

The next year crops had been good until late in the summer, and Mormons were looking forward to a winter with enough to eat. But one day clouds of crickets so black they made the day like night came out of the sky and feel to devouring the crops like a fire. Neither beating, flooding, burning, nor praying seemed to have any effect on the crickets. Then one day, as suddenly and as mysteriously as the crickets had come, there appeared clouds of large white seagulls from the banks of the Great Salt Lake. These gulls fell upon the crickets, eating and disgorging them on the spot until the plague was wiped out and some of the crops were saved. The legend of the seagull is one of the greatest in Mormon history. It is firmly believed that the gulls were sent by God to protect His people. Since that time the seagull is protected in Utah, and a great monument stands on the corner of Main and South Temple streets in Salt Lake City.

The next three years were a little less free from want than had been the previous years, and by the time Benjamin entered the valley late in the summer of 1852 the crops were green with the promise of food for the winter. The Mansfields were apportioned a small plot of land some distance from the community center; then they set to work to build a log cabin in one of the blocks of the well-laid city. It was the custom of the early Mormon settlers to live close together and to go out around the edges of the settlement to their farms. Here was communal living highly developed and successful.

While Benjamin helped his foster father cut and haul heavy logs from City Creek canyon and lay them into place for a one-room house with one window, covered with hide, and a door so small that even the boy had to stoop to get through it to the packed dirt floor within, the National Congress in Washington had finally decided, because of the scare from the quarrel with Mexico, to grant the petition that the Mormon Center become a Territory. They eliminated the proposed name of Deseret because it came from the Book of Mormon, and substituted the name of Utah, after the Ute Indians. So that year Benjamin helped to build one more cabin in what was beginning to be an integral part of a great Nation, the Territory of Utah.

It was the custom of the Mormon Church to "call" certain persons and families to go into different portions of the Territory to colonize. Often it was very difficult to leave the comparative comfort that one's labors had built and go into a barren land to begin anew.

It was a sore test of religious faith. But in 1853 the Mansfields answered the "Call" to go to Millcreek to help establish a new colony there. Millcreek was located only a short distance south and east of Salt Lake City, but at that time it was remote enough.to require a new colony.

Here once again Benjamin took the place of a man in building a shelter and planting a crop. These were desperate years for all in the Territory of Utah, but especially were they hard for new colonists. The specter of starvation was always before them during the long winters, and always the never-ending struggle to keep alive in a land that seemed hostile by nature to man. Benjamin's mother and brother had not yet arrived from St. Louis, and he was desperately lonely for his family, but at ten Benjamin was a man; he had never been a boy since he had left New York. And now he carried a man's burdens and felt with a man's emotions. And always he worked bitterly hard. Life was a never-ending battle in this land of outrageous hostility.

Everything about Utah seemed to defy man. Its endless stretches of empty white alkali deserts stretching off into a briny bitter body of water that defied any life within or around it, its steep mountains of vicious crags and great canyons, barren for the most part, but at best yielding little in timber for the terrific effort required to get it out. There were wild murderous winters, and long sweltering summers, and always the question of precious water to irrigate the parched land, which would not be broken until it had drunk its fill. And behind all this there were hosts of living enemies: rattlesnakes, coyotes, bear, wildcats, grasshoppers, tarantulas, and Indians.

But there was another side to this wild, unbridled land. It was at once a challenge and a blessing. Benjamin grew up among a people that had been tempered by a desperate struggle for life; a people who knew what it was to look starvation in the face for long, cold months and still carry on. Only intense religious zeal will give men such courage. That is why they were able to conquer the desert. They believed in "faith with works," and they starved on thistle roots, sage-lily bulbs, hawks , owls, crows and mice, while they clung stubbornly to the land -- and conquered it. And even in the midst of such struggle they poured out something of a cry of exultation, a mass hymn of praise for the land with which they were in mortal conflict. Many of the religious songs appeared at this time, a number of them in the form of odes to the land in which they lived.

It was in 1854 that Benjamin first got his taste of Indian fighting, or rather of protecting himself from the Indians. The "Walker war" was a series of skirmishes between the Mormons and the Ute Indians under the leadership of Chief Wakara (Walker).

It came about because the territorial legislature of Utah passed a law to prohibit the white slave traffic among the Ute Indians. These fierce red warriors had for years been raiding other Indian tribes, and occasionally white settlements, stealing their women and selling them to the Spaniards in Mexico. In 1893 Chief Wakara, incensed at the Mormon interference, led a raid on Springville, a town about fifty miles south of Salt Lake. This was followed by several other fierce raids on other small settlements in that region. As a matter of self- preservation, the Mormon settlements in these parts hastily built forts in which they could take refuge from such raids. Upon Millcreek the Mansfields and Benjamin worked feverishly to help finish a stockade before an attack should come on them. And when it did come, they were ready. Millcreek was saved, with most of its stock and food, and Benjamin saw for the first time human beings groveling in the dust in the agonies of death. There must have been some thing in that first experience with the Indians to touch that serious-minded boy deeply, for later he became a great friend of the Indians and a peacemaker between them and the settlers.

In the next ten years Benjamin saw some amazing things happen in and around the Territory. Some of these events are difficult to believe even though long since established as fact. While the Mormons wanted nothing except to be left alone to go about their business of wresting a living from a hostile environment, the outside world would not be content to stop persecuting them even in their mountain isolation. Many incidents occurred to stir the troubled relations. In the same year that the Walker War was settled a Government Surveyor by the name of Gunnison was killed, with most of his party, by Indians in southern Utah. outsiders blamed the Mormons for setting the Indians upon the party; the charge was later proved untrue, but many believed it. Then the horrible Mountain Meadows massacre, in which 120 of a party of Arkansans, traveling to California, were murdered by Indians, or by Indians and white men dressed as Indians. There has been considerable evidence to indicate that Mormons may have participated in the massacre or even perpetrated it.

Only one man was ever brought to justice for it; he was a Mormon Bishop at the time the killing took place, John D. Lee.

In 1854 Benjamin had helped his foster family fight another grasshopper infestation, and had seen the specter of starvation for another winter. The year following almost all crops were destroyed by grasshoppers, and settlers lived through the year by the barest margin. The year after that, famine conditions prevailed through all the territory, and many died of starvation.

That same year the Tintic war with the Ute Indians was fought in Utah and Cedar Valleys, and Mr. Mansfield was called away from his farm for several months to help the volunteers from other settlements in this "war."

It had been a most difficult time for Margaret Mitchell Lillywhite since her husband and daughter had died. Not long after coming to Salt Lake Valley she had received word from a maiden Aunt in England asking her to return home to claim a large fortune to which she was rightful heir. She borrowed money and returned with Joseph to England. Once there she found that the fortune could be hers only upon the condition that she renounce her Mormon religion and remain in England. It was a difficult decision. Margaret Lillywhite had suffered the extreme of poverty. She looked at what seemed to be her obligation to her two sons as opposed to her obligation to her God. But as she studied over the matter she was surprised to discover that both obligations merged into one; there was no conflict, so she renounced neither her God nor her sons, but her fortune. And once again she and Joseph turned their faces west toward the new land of Zion where they had caught a brief glimpse of the spirit of freedom and the surging progress that blew like a fresh clean breeze across her English background of class privilege and prejudice.

So in 1857 Mrs. Lillywhite and Joseph returned to great Salt Lake City. They saw Benjamin shortly, but his mother was too poor to reclaim him, and he was too much grown to come home. Not long after her return Mrs. Lillywhite married Sam Eldridge, a farmer in Salt Lake Valley. When the Mormons were having difficulties with the Government and they thought Salt Lake might be burned rather than letting the "foreigners" have it, the Eldridges moved to Parowan in southern Utah. Later, when peace was established, they moved back up north to Fillmore and made their home there. In 1860 Mr. Eldridge died, leaving Joseph and his mother again facing hunger. They moved to Beaver where Joseph worked on a dairy farm.

In 1860 Benjamin left his foster parents and traded his horse for forty acres of land and squatters rights at North Creek. He was again near his mother and brother, but never did live with them.

In 1863 the immigrant family of Lewis of South Wales came to Beaver. Benjamin met and fell in love with their pretty daughter Mary. On Christmas Day of 1865 they were married in the Church Endowment House. A short time later Benjamin's mother also married again; this time her husband was Elijah Elmer, a farmer living south of Beaver.

That same year the Congregationalists established the first non-Mormon Church in Utah and shocked the Mormons into a realization that they were no longer alone.

Then, late in the fall, the Ute Black Hawk War broke out; this was an uprising of the Ute Indians in eastern Utah. Almost before he knew he was married, Benjamin found himself a member of a volunteer army called "minute men" and pledged to protect white settlers from the rampaging Utes. Benjamin served in Company Two under Captain Joseph Betterson. They were stationed at Fort Sanford on the Sevier River. Each company in this motley army served alternately for thirty days; then for thirty days they would go home and look after their crops and families while another company took over. It was here that Benjamin learned more about the ways of the red man, and gained considerable sympathy for them, though he had a healthy respect for their potentialities for mischief when on the war path. During one of his thirty-day leaves Benjamin returned to Beaver to find that his wife Mary was not having an easy time keeping his forty acres running, that the Utes were a constant menace to settlers right here at home, and that his brother Joseph was at that moment lying critically ill from a bullet wound fired by a raiding Indian.

Joseph had worked for some years on the dairy farm on Birch Creek ten miles south of Beaver. This farm was owned by Punkin Lee, brother of John D. Lee of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. One morning just at dawn Joseph opened the door of the Lee cabin to go to the barn. As he stepped out of the door a shot rang out and he fell to the ground with a bullet through his shoulder. Immediately the woods surrounding the house burst into a frenzy of gunfire and the wild shouts of Ute Indian raiders. Joseph managed to crawl back into the house before he collapsed.

The Indians closed in on the house, shooting wildly at doors and windows. They tried to set fire to the house, but the gunfire from the men inside prevented it. After some hours of fighting the situation looked hopeless to the whites. In desperation they took an almost unbelievable chance. Two children of the Lees, Reuben, twelve, and Rose, eight, were put through a back window of the cabin with instructions to try to get to Beaver ten miles away for help, if they could escape the Indians. By some miracle they did get through and headed for Beaver. Soon Rose could go no further, so Reuben concealed her in a clump of sagebrush and went on. In Beaver the exhausted boy found most of the men working on the new Church house. They were all armed, as a precaution against Indians, and their horses were tied to the hitching posts. So in a short time they were off to the rescue, with the courageous Reuben on a horse behind one of the men. On the way they stopped and got Rose, who was almost paralyzed with fear.

While the rescue party was on its way, the battle at the Lees became more critical. At one time the Indians threw a lighted torch through a window and it caught fire on the curtains and rag carpets. There was no water in the house, and no one could get to the well outside. This time Mrs. Lee came to the rescue with pans of milk set out in the corner of the room from the last night's milking. The house was saved from fire just at the moment that men from town arrived and drove the Indians off. It was none too soon to save the life of Joseph, who had been bleeding considerably throughout the day. But he did partially recover from his wound. Years later it was the indirect cause of his death.

In January 1867 Mary Lewis Lillywhite gave birth to her first child, a daughter named Catherine. Later the same year the Salt Lake Tabernacle was completed, grasshoppers made a new onslaught on the crops of the Mormons, and Benjamin Lillywhite returned home from the Ute Black Hawk War no richer, but much wiser. Benjamin came from the trouble with the Indians to a different kind of trouble at home. He found the once peaceful village of Beaver now turned into a brawling camp of miners who rode roughshod over the Mormon settlers. The early settlers had paid little attention to the arid mountains west of Beaver, but outsiders had dug in them and found "riches" which the Mormons promptly labeled "coin of the devil."

There was a brief boom and prosperity for business in Beaver, but there was misery and mistreatment, suspicion and hatred for the farmers and their families. Lust and licentiousness erupted the peace of the little town. The drunken miners paid no attention to decencies, and any woman was considered fair game, especially if she were a daughter or wife of the hated Mormons.

But Benjamin's attention was upon his forty acres west of Beaver, his pretty young wife, and their daughter, rather than upon the wickedness of the miners. He set to work 'energetically to make a living for them all. Not long after his return from the "war" he landed a job as a mail clerk for the Government, his task being to deliver mail by ox or horse team between Fillmore and Cedar City. This was a long and hazardous route, subject to Indian raids at any time. But it was during this period that Benjamin won the respect and protection of the Indians rather than their enmity. His farm became a haven for many of the red men. In winter they would pitch tents on his farm and then trade him buckskins and other goods for food. They came to him to settle their troubles and heal their sick.

He became· their white friend because he learned to speak their tongue and to sympathize with their problems. As a consequence, he never lost a pound of mail or freight in all his years on the road.

In 1869 a second daughter, Isabelle, was born to Benjamin and Mary. At the same time the mining boom in Beaver slackened considerably as the ore began to play out. In Salt Lake City the U. S. Land Office was opened, making it possible for Utahans to get title to their lands. Benjamin bought another forty acres next to his first forty; this spot grew into one of the best farms in an excellent farming community. This year also Benjamin's brother, Joseph, took a wife, and almost immediately was "called" to help colonize in Old Mexico. He went, and never again did he see Benjamin or his mother, even after he and his family were finally driven out of Mexico, in one of its numerous revolutions, and settled in Arizona's Salt River Valley.

Benjamin and Mary worked hard and prospered moderately. The serious, tall, thin young man was beginning to be recognized as a leader in his Church and a valuable community agent in making peace with the Indians. And the Indians recognized him as a friend and a man who could keep his word. The social life of Beaver was never dull, and Benjamin and Mary took part as much as their time and growing family would allow.

Benjamin became a member of the famous Beaver Choir and Brass Band, and Mary took part in the newly-organized Beaver Dramatic Society, all under the direction of Robert Stoney, former Leeds needle maker, who had just returned from Minersville a short time before, where he had gone to live with his family. Mr. Stoney's musical accomplishments had become so much favored that a few years previously citizens of Minersville had offered Robert a gift of five acres of cleared land if he would move his family there and organize a Church choir. This he had done, but while in Minersville the Stoneys' baby, John, had become ill and it was Mrs. Stoney's firm belief that if they would return to Beaver the baby would live. So they moved back to Beaver and the baby's life was spared.

In January of 1872 twins were born to Mary Lillywhite. One died, but the one that lived was a healthy squalling son, later taken to Church, given a blessing, and christened Joseph Henry. A year and three months after the firth of Joseph a daughter was born to Robert and Sarah Stoney, the sixth child in what became a family of ten.

She was named Elizabeth Ellen, blessed and christened in the same church as Joseph had been Destiny had already linked these two together.

In 1872 several other pretentious events took place. The first street car system opened in Salt Lake City. The war over polygamy raged with increasing fury in and out of the Territory, and talk of the united Order of Enoch was rife. The Territory was undergoing growing pains and the strange Mormon beliefs were once more being tested. It was difficult in 1874 for Benjamin to bring himself to join the United Order of Enoch that Brigham Young had ordered though out the Territory. This was a plan of communal living so advanced that other societies had not dared even to think of it up to that time. All goods were to be voluntarily turned in to a central storehouse from which food and clothing and other necessities were dispensed to all, according to need. Men were given credit for the amount of goods they turned in, but it was difficult for many of them to see where there was any other benefit derived.

Benjamin Lillywhite Jr. in 1939 with Janet, Marilyn, Jeanne, David and Dick, his great grandchildren.

It was impossible for the mother to remain in St. Louis with her two sons, so she arranged to take Joseph to Utah with a wagon train, but there was not room for three. Consequently, Benjamin was adopted by a couple named Miller, under whose care he began the trip to Utah in a different wagon train. On the plains of Iowa Mr. Miller died, and Benjamin, now nine, drove the ox team the remainder of the trip to Salt Lake Valley, arriving there in September 1852.

Mrs. Miller accepted the practical suggestion of her church leaders to waste no time in grieving or in finding another husband, so she married Mathew Mansfield late that same year. Benjamin remained with the Mansfields until after he was seventeen.

When the Mormons were driven out of Nauvoo, Brigham Young had turned his face to the west with the statement, "If there is a place no one else will have, that is the place I am looking for." In 1852 "Zion" must have appeared, to the new arrivals, like the place no one would have. In the first year of its settlement, 1847, nearly all the work of the settlers had been destroyed overnight by a heavy frost, and later what was left was eaten by crickets. Hunger had stalked every door during that long winter.

The next year crops had been good until late in the summer, and Mormons were looking forward to a winter with enough to eat. But one day clouds of crickets so black they made the day like night came out of the sky and feel to devouring the crops like a fire. Neither beating, flooding, burning, nor praying seemed to have any effect on the crickets. Then one day, as suddenly and as mysteriously as the crickets had come, there appeared clouds of large white seagulls from the banks of the Great Salt Lake. These gulls fell upon the crickets, eating and disgorging them on the spot until the plague was wiped out and some of the crops were saved. The legend of the seagull is one of the greatest in Mormon history. It is firmly believed that the gulls were sent by God to protect His people. Since that time the seagull is protected in Utah, and a great monument stands on the corner of Main and South Temple streets in Salt Lake City.

The next three years were a little less free from want than had been the previous years, and by the time Benjamin entered the valley late in the summer of 1852 the crops were green with the promise of food for the winter. The Mansfields were apportioned a small plot of land some distance from the community center; then they set to work to build a log cabin in one of the blocks of the well-laid city. It was the custom of the early Mormon settlers to live close together and to go out around the edges of the settlement to their farms. Here was communal living highly developed and successful.

While Benjamin helped his foster father cut and haul heavy logs from City Creek canyon and lay them into place for a one-room house with one window, covered with hide, and a door so small that even the boy had to stoop to get through it to the packed dirt floor within, the National Congress in Washington had finally decided, because of the scare from the quarrel with Mexico, to grant the petition that the Mormon Center become a Territory. They eliminated the proposed name of Deseret because it came from the Book of Mormon, and substituted the name of Utah, after the Ute Indians. So that year Benjamin helped to build one more cabin in what was beginning to be an integral part of a great Nation, the Territory of Utah.

It was the custom of the Mormon Church to "call" certain persons and families to go into different portions of the Territory to colonize. Often it was very difficult to leave the comparative comfort that one's labors had built and go into a barren land to begin anew.

It was a sore test of religious faith. But in 1853 the Mansfields answered the "Call" to go to Millcreek to help establish a new colony there. Millcreek was located only a short distance south and east of Salt Lake City, but at that time it was remote enough.to require a new colony.

Here once again Benjamin took the place of a man in building a shelter and planting a crop. These were desperate years for all in the Territory of Utah, but especially were they hard for new colonists. The specter of starvation was always before them during the long winters, and always the never-ending struggle to keep alive in a land that seemed hostile by nature to man. Benjamin's mother and brother had not yet arrived from St. Louis, and he was desperately lonely for his family, but at ten Benjamin was a man; he had never been a boy since he had left New York. And now he carried a man's burdens and felt with a man's emotions. And always he worked bitterly hard. Life was a never-ending battle in this land of outrageous hostility.

Everything about Utah seemed to defy man. Its endless stretches of empty white alkali deserts stretching off into a briny bitter body of water that defied any life within or around it, its steep mountains of vicious crags and great canyons, barren for the most part, but at best yielding little in timber for the terrific effort required to get it out. There were wild murderous winters, and long sweltering summers, and always the question of precious water to irrigate the parched land, which would not be broken until it had drunk its fill. And behind all this there were hosts of living enemies: rattlesnakes, coyotes, bear, wildcats, grasshoppers, tarantulas, and Indians.

But there was another side to this wild, unbridled land. It was at once a challenge and a blessing. Benjamin grew up among a people that had been tempered by a desperate struggle for life; a people who knew what it was to look starvation in the face for long, cold months and still carry on. Only intense religious zeal will give men such courage. That is why they were able to conquer the desert. They believed in "faith with works," and they starved on thistle roots, sage-lily bulbs, hawks , owls, crows and mice, while they clung stubbornly to the land -- and conquered it. And even in the midst of such struggle they poured out something of a cry of exultation, a mass hymn of praise for the land with which they were in mortal conflict. Many of the religious songs appeared at this time, a number of them in the form of odes to the land in which they lived.

It was in 1854 that Benjamin first got his taste of Indian fighting, or rather of protecting himself from the Indians. The "Walker war" was a series of skirmishes between the Mormons and the Ute Indians under the leadership of Chief Wakara (Walker).

It came about because the territorial legislature of Utah passed a law to prohibit the white slave traffic among the Ute Indians. These fierce red warriors had for years been raiding other Indian tribes, and occasionally white settlements, stealing their women and selling them to the Spaniards in Mexico. In 1893 Chief Wakara, incensed at the Mormon interference, led a raid on Springville, a town about fifty miles south of Salt Lake. This was followed by several other fierce raids on other small settlements in that region. As a matter of self- preservation, the Mormon settlements in these parts hastily built forts in which they could take refuge from such raids. Upon Millcreek the Mansfields and Benjamin worked feverishly to help finish a stockade before an attack should come on them. And when it did come, they were ready. Millcreek was saved, with most of its stock and food, and Benjamin saw for the first time human beings groveling in the dust in the agonies of death. There must have been some thing in that first experience with the Indians to touch that serious-minded boy deeply, for later he became a great friend of the Indians and a peacemaker between them and the settlers.

In the next ten years Benjamin saw some amazing things happen in and around the Territory. Some of these events are difficult to believe even though long since established as fact. While the Mormons wanted nothing except to be left alone to go about their business of wresting a living from a hostile environment, the outside world would not be content to stop persecuting them even in their mountain isolation. Many incidents occurred to stir the troubled relations. In the same year that the Walker War was settled a Government Surveyor by the name of Gunnison was killed, with most of his party, by Indians in southern Utah. outsiders blamed the Mormons for setting the Indians upon the party; the charge was later proved untrue, but many believed it. Then the horrible Mountain Meadows massacre, in which 120 of a party of Arkansans, traveling to California, were murdered by Indians, or by Indians and white men dressed as Indians. There has been considerable evidence to indicate that Mormons may have participated in the massacre or even perpetrated it.

Only one man was ever brought to justice for it; he was a Mormon Bishop at the time the killing took place, John D. Lee.

In 1854 Benjamin had helped his foster family fight another grasshopper infestation, and had seen the specter of starvation for another winter. The year following almost all crops were destroyed by grasshoppers, and settlers lived through the year by the barest margin. The year after that, famine conditions prevailed through all the territory, and many died of starvation.

That same year the Tintic war with the Ute Indians was fought in Utah and Cedar Valleys, and Mr. Mansfield was called away from his farm for several months to help the volunteers from other settlements in this "war."

It had been a most difficult time for Margaret Mitchell Lillywhite since her husband and daughter had died. Not long after coming to Salt Lake Valley she had received word from a maiden Aunt in England asking her to return home to claim a large fortune to which she was rightful heir. She borrowed money and returned with Joseph to England. Once there she found that the fortune could be hers only upon the condition that she renounce her Mormon religion and remain in England. It was a difficult decision. Margaret Lillywhite had suffered the extreme of poverty. She looked at what seemed to be her obligation to her two sons as opposed to her obligation to her God. But as she studied over the matter she was surprised to discover that both obligations merged into one; there was no conflict, so she renounced neither her God nor her sons, but her fortune. And once again she and Joseph turned their faces west toward the new land of Zion where they had caught a brief glimpse of the spirit of freedom and the surging progress that blew like a fresh clean breeze across her English background of class privilege and prejudice.

So in 1857 Mrs. Lillywhite and Joseph returned to great Salt Lake City. They saw Benjamin shortly, but his mother was too poor to reclaim him, and he was too much grown to come home. Not long after her return Mrs. Lillywhite married Sam Eldridge, a farmer in Salt Lake Valley. When the Mormons were having difficulties with the Government and they thought Salt Lake might be burned rather than letting the "foreigners" have it, the Eldridges moved to Parowan in southern Utah. Later, when peace was established, they moved back up north to Fillmore and made their home there. In 1860 Mr. Eldridge died, leaving Joseph and his mother again facing hunger. They moved to Beaver where Joseph worked on a dairy farm.

In 1860 Benjamin left his foster parents and traded his horse for forty acres of land and squatters rights at North Creek. He was again near his mother and brother, but never did live with them.

In 1863 the immigrant family of Lewis of South Wales came to Beaver. Benjamin met and fell in love with their pretty daughter Mary. On Christmas Day of 1865 they were married in the Church Endowment House. A short time later Benjamin's mother also married again; this time her husband was Elijah Elmer, a farmer living south of Beaver.

That same year the Congregationalists established the first non-Mormon Church in Utah and shocked the Mormons into a realization that they were no longer alone.

Then, late in the fall, the Ute Black Hawk War broke out; this was an uprising of the Ute Indians in eastern Utah. Almost before he knew he was married, Benjamin found himself a member of a volunteer army called "minute men" and pledged to protect white settlers from the rampaging Utes. Benjamin served in Company Two under Captain Joseph Betterson. They were stationed at Fort Sanford on the Sevier River. Each company in this motley army served alternately for thirty days; then for thirty days they would go home and look after their crops and families while another company took over. It was here that Benjamin learned more about the ways of the red man, and gained considerable sympathy for them, though he had a healthy respect for their potentialities for mischief when on the war path. During one of his thirty-day leaves Benjamin returned to Beaver to find that his wife Mary was not having an easy time keeping his forty acres running, that the Utes were a constant menace to settlers right here at home, and that his brother Joseph was at that moment lying critically ill from a bullet wound fired by a raiding Indian.

Joseph had worked for some years on the dairy farm on Birch Creek ten miles south of Beaver. This farm was owned by Punkin Lee, brother of John D. Lee of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. One morning just at dawn Joseph opened the door of the Lee cabin to go to the barn. As he stepped out of the door a shot rang out and he fell to the ground with a bullet through his shoulder. Immediately the woods surrounding the house burst into a frenzy of gunfire and the wild shouts of Ute Indian raiders. Joseph managed to crawl back into the house before he collapsed.

The Indians closed in on the house, shooting wildly at doors and windows. They tried to set fire to the house, but the gunfire from the men inside prevented it. After some hours of fighting the situation looked hopeless to the whites. In desperation they took an almost unbelievable chance. Two children of the Lees, Reuben, twelve, and Rose, eight, were put through a back window of the cabin with instructions to try to get to Beaver ten miles away for help, if they could escape the Indians. By some miracle they did get through and headed for Beaver. Soon Rose could go no further, so Reuben concealed her in a clump of sagebrush and went on. In Beaver the exhausted boy found most of the men working on the new Church house. They were all armed, as a precaution against Indians, and their horses were tied to the hitching posts. So in a short time they were off to the rescue, with the courageous Reuben on a horse behind one of the men. On the way they stopped and got Rose, who was almost paralyzed with fear.

While the rescue party was on its way, the battle at the Lees became more critical. At one time the Indians threw a lighted torch through a window and it caught fire on the curtains and rag carpets. There was no water in the house, and no one could get to the well outside. This time Mrs. Lee came to the rescue with pans of milk set out in the corner of the room from the last night's milking. The house was saved from fire just at the moment that men from town arrived and drove the Indians off. It was none too soon to save the life of Joseph, who had been bleeding considerably throughout the day. But he did partially recover from his wound. Years later it was the indirect cause of his death.

In January 1867 Mary Lewis Lillywhite gave birth to her first child, a daughter named Catherine. Later the same year the Salt Lake Tabernacle was completed, grasshoppers made a new onslaught on the crops of the Mormons, and Benjamin Lillywhite returned home from the Ute Black Hawk War no richer, but much wiser. Benjamin came from the trouble with the Indians to a different kind of trouble at home. He found the once peaceful village of Beaver now turned into a brawling camp of miners who rode roughshod over the Mormon settlers. The early settlers had paid little attention to the arid mountains west of Beaver, but outsiders had dug in them and found "riches" which the Mormons promptly labeled "coin of the devil."

There was a brief boom and prosperity for business in Beaver, but there was misery and mistreatment, suspicion and hatred for the farmers and their families. Lust and licentiousness erupted the peace of the little town. The drunken miners paid no attention to decencies, and any woman was considered fair game, especially if she were a daughter or wife of the hated Mormons.

But Benjamin's attention was upon his forty acres west of Beaver, his pretty young wife, and their daughter, rather than upon the wickedness of the miners. He set to work 'energetically to make a living for them all. Not long after his return from the "war" he landed a job as a mail clerk for the Government, his task being to deliver mail by ox or horse team between Fillmore and Cedar City. This was a long and hazardous route, subject to Indian raids at any time. But it was during this period that Benjamin won the respect and protection of the Indians rather than their enmity. His farm became a haven for many of the red men. In winter they would pitch tents on his farm and then trade him buckskins and other goods for food. They came to him to settle their troubles and heal their sick.

He became· their white friend because he learned to speak their tongue and to sympathize with their problems. As a consequence, he never lost a pound of mail or freight in all his years on the road.

In 1869 a second daughter, Isabelle, was born to Benjamin and Mary. At the same time the mining boom in Beaver slackened considerably as the ore began to play out. In Salt Lake City the U. S. Land Office was opened, making it possible for Utahans to get title to their lands. Benjamin bought another forty acres next to his first forty; this spot grew into one of the best farms in an excellent farming community. This year also Benjamin's brother, Joseph, took a wife, and almost immediately was "called" to help colonize in Old Mexico. He went, and never again did he see Benjamin or his mother, even after he and his family were finally driven out of Mexico, in one of its numerous revolutions, and settled in Arizona's Salt River Valley.

Benjamin and Mary worked hard and prospered moderately. The serious, tall, thin young man was beginning to be recognized as a leader in his Church and a valuable community agent in making peace with the Indians. And the Indians recognized him as a friend and a man who could keep his word. The social life of Beaver was never dull, and Benjamin and Mary took part as much as their time and growing family would allow.

Benjamin became a member of the famous Beaver Choir and Brass Band, and Mary took part in the newly-organized Beaver Dramatic Society, all under the direction of Robert Stoney, former Leeds needle maker, who had just returned from Minersville a short time before, where he had gone to live with his family. Mr. Stoney's musical accomplishments had become so much favored that a few years previously citizens of Minersville had offered Robert a gift of five acres of cleared land if he would move his family there and organize a Church choir. This he had done, but while in Minersville the Stoneys' baby, John, had become ill and it was Mrs. Stoney's firm belief that if they would return to Beaver the baby would live. So they moved back to Beaver and the baby's life was spared.

In January of 1872 twins were born to Mary Lillywhite. One died, but the one that lived was a healthy squalling son, later taken to Church, given a blessing, and christened Joseph Henry. A year and three months after the firth of Joseph a daughter was born to Robert and Sarah Stoney, the sixth child in what became a family of ten.

She was named Elizabeth Ellen, blessed and christened in the same church as Joseph had been Destiny had already linked these two together.

In 1872 several other pretentious events took place. The first street car system opened in Salt Lake City. The war over polygamy raged with increasing fury in and out of the Territory, and talk of the united Order of Enoch was rife. The Territory was undergoing growing pains and the strange Mormon beliefs were once more being tested. It was difficult in 1874 for Benjamin to bring himself to join the United Order of Enoch that Brigham Young had ordered though out the Territory. This was a plan of communal living so advanced that other societies had not dared even to think of it up to that time. All goods were to be voluntarily turned in to a central storehouse from which food and clothing and other necessities were dispensed to all, according to need. Men were given credit for the amount of goods they turned in, but it was difficult for many of them to see where there was any other benefit derived.

Each man worked his land or pursued his trade for the good of the community, not for his own enrichment. Benjamin had made a good start with his homestead, and it was not in his nature to give it up so easily. His friend, Robert Stoney, on the other hand, readily accepted the idea and urged Benjamin to do likewise. It is possible that the difference in the attitudes of the two men came from the fact that Robert was older than Benjamin and owned very little

property at that time. But in the end both gave up all they had and joined the United Order.

Men did retain title to their lands, so the farm was not lost to Benjamin. In 1877 Robert Stoney's Choir and Band took part in the dedication of the St. George Temple. Benjamin drove his team and wagon and a load of singers to the dedication. On April 6 the Beaver Choir, led by Robert, and with Benjamin among the singers, won warm words of praise from President Young and other speakers.

During the next ten years Benjamin became a Mormon Bishop and a civic leader, and continued to prosper moderately, and his family grew at the rate of a son or daughter every two years. Robert Stoney became more active with his musical work, but did not prosper

greatly.

In 1888 Margaret Mitchell Elmer, mother of Benjamin and Joseph Lillywhite, and of Horace, Elijah, and Sarah Elmer, died in Beaver at the age of sixty-six.

In 1891 Benjamin declared himself a member of the newly-created Democratic party in Utah in opposition to the new Republican party. In 1895 Benjamin and his sons fought desperately against a terrible crop failure. In 1896 when Utah became the forty-fifth state in the Union, and they should have been rejoicing, the situation became even more desperate.

For the second successive year crops were wiped out by drought and there was nothing left to harvest. So in the spring of 1897 Benjamin and his 'family settled in the northern Utah valley of Riverside, but a short time later followed their son Joseph and settled in Brigham City. While chopping wood one day Benjamin was struck in the eye by a flying chip. In spite of all the care they could give it, a malignant growth developed, from which he eventually lost the sight of one eye completely.

Men did retain title to their lands, so the farm was not lost to Benjamin. In 1877 Robert Stoney's Choir and Band took part in the dedication of the St. George Temple. Benjamin drove his team and wagon and a load of singers to the dedication. On April 6 the Beaver Choir, led by Robert, and with Benjamin among the singers, won warm words of praise from President Young and other speakers.

During the next ten years Benjamin became a Mormon Bishop and a civic leader, and continued to prosper moderately, and his family grew at the rate of a son or daughter every two years. Robert Stoney became more active with his musical work, but did not prosper

greatly.

In 1888 Margaret Mitchell Elmer, mother of Benjamin and Joseph Lillywhite, and of Horace, Elijah, and Sarah Elmer, died in Beaver at the age of sixty-six.

In 1891 Benjamin declared himself a member of the newly-created Democratic party in Utah in opposition to the new Republican party. In 1895 Benjamin and his sons fought desperately against a terrible crop failure. In 1896 when Utah became the forty-fifth state in the Union, and they should have been rejoicing, the situation became even more desperate.

For the second successive year crops were wiped out by drought and there was nothing left to harvest. So in the spring of 1897 Benjamin and his 'family settled in the northern Utah valley of Riverside, but a short time later followed their son Joseph and settled in Brigham City. While chopping wood one day Benjamin was struck in the eye by a flying chip. In spite of all the care they could give it, a malignant growth developed, from which he eventually lost the sight of one eye completely.

In 1914 his wife Mary died, leaving Benjamin so completely alone that he seemed unable to adjust to life.

Benjamin's life, except for the physiological processes, almost stopped with the death of Mary. He went 'through the motions of living, but he longed to be with her on the other side; he too was tired. For a time he tried to live alone, but his life was terribly empty.

Then he went to work in the Temple at Salt Lake City. Here he found an older woman whom he thought might be a companion for him.

They were married, but it was only a few years before both found that they were too old and too helpless to be of any assistance to each other; she was much more of a cripple than he.

So Benjamin parted from his second wife, and each went to live with their children. Benjamin lived with his son Joseph and his third wife Marie from 1933 in this death in 1939.

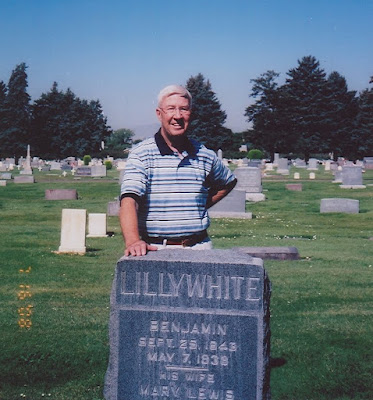

Tombstone of Benjamin Lillywhite, Jr. and Mary Lewis which is in Brigham City, Utah. David Anderson, great grandson, is standing behind the tombstone.